|

| Tomas Saraceno, Cumulus at Barbican |

↓↓↓

Some time ago I wrote a post digitised scrolls: from the Pond at Deuchar to the Trip to London, at the bottom of which I mentioned a charming Georgian device Trip to London that had been digitised by Princeton University. Trip to London is a box containing a twelve plate scroll that displays a humorous story of a honeymoon trip. It is a close development of the very popular moving panoramas, which came to Europe in late 17th century and by early 19th century they were so common, that there were even ladies' fans with miniature scrolled pictures incorporated into the designs.

|

| Trip to London |

↓↓↓

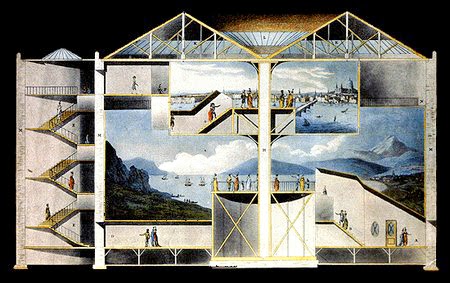

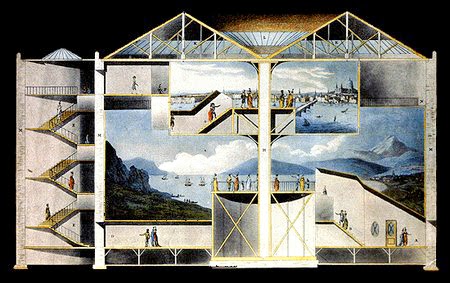

Moving panorama - to put it simply - is a long panorama in a scroll, which has ends of it attached to two rods. The handles on the rods are then turned to allow the panorama to move across the screen, very much like a basic animation film. Moving panoramas were available in handheld scrolling devices as well as a form of large screen/stage entertainment. They were hugely popular: successful shows drew crowds and boasted years of performances. For example, Albert Smith's Ascent of Mont Blanc was performed for seven years at the Egyptian Hall in London, while Hugo d'Alesi's Mareorama allowed seven hundred spectators per viewing of this show, that offered a multisensory sea voyage illusion, complete with thunder, wind and local dancers.

|

| a card promoting Hugo d'Alesi's Mareorama |

Moving panoramas were extraordinary pieces of

engineering. They often featured special enhanced sets and effects,

merging of medias and mediums into one immersive spectacle. For example, touring

panoramas of the late nineteen century England frequently included such

novelties as mechanical puppets and slide projections. The most

impressive ones, of course, were present at Exposition Universelle in Paris, 1900. The above mentioned Hugo d'Alesi's Mareorama incorporated two screens, each 2,500 feet long and forty feet in height, which were scrolled for the viewers present on board of the full size boat. The boat required hydraulic piston engines and pumps driven by electric motors to stimulate motion.

|

| Hugo d'Alesi's Mareorama |

|

| Hugo d'Alesi's Mareorama |

Another immersive panorama at Exposition Universelle in Paris was Pavel Yakovlevich Pyasetsky's Great Siberian Railway Panorama in the Russian pavilion. It offered a 45 minute experience of Trans Siberian rail journey complete with stuffed polar bears on papier-mache icebergs, a dinner of caviar and sturgeon in a luxury imitation train with a library, gymnasium, marble bath, smoking and music salons.

This 45-minute experience was an essay

in detail. It offered a chance to experience the 14-day journey by rail

from Moscow to Peking, a 6300-mile journey over tracks not yet completed

at the time of the Paris Fair of 1900.

There were three realistic railway cars, each 70 feet

long, with saloons, dining rooms, bars, bedrooms, and other elements of a

luxury train. Totally detailed and lavishly equipped, the cars were

elevated a little above a place for spectators in conventional rows of

seats. The gallery faced a stage-like arena where the simulated views

along the train trip were presented by an inventive contraption.

The immediate reality of a vehicular trip is that

nearby objects seem to pass by more rapidly than distant ones. So,

nearest to the participants was a horizontal belt covered with sand,

rocks, and boulders, driven at a speed of 1000 feet per minute! Behind

that was a low vertical screen painted with shrubs and brush, travelling

at 400 feet per minute. A second, slightly higher screen, painted to

show more distant scenery, scrolled along at 130 feet per minute. The

most distant one, 25 feet tall and 350 feet long painted with mountains,

forests, clouds and cities, moved at 16 feet per minute.

Real geographical features along the way were depicted

on this screen: Moscow, Omsk, Irkutsk, the shores of great lakes and

rivers, the Great Wall of China, and Peking. The screens, moving in one

direction only, were implemented as a belt system. Due to the inexact

speeds of the scenery,the 'journey' never repeated itself exactly,

providing an ever-changing combination of scenes and a reason to pay to

see the attraction again. (from The Past Was No Illusion by Walt Bransford)

|

| Pavel Yakovlevich Pyasetsky's Great Siberian Railway Panorama |

↓↓↓

Apart from the great spectacles at Exposition Universelle, 1900, there was a range of other - more common and more humble - weird and wonderful panorama devices. There existed pleoramas, dioramas, padoramas, myrioramas, phantom rides for public viewing as well as personal hand panorama reels, magic lanterns and peep-shows.

|

| The Kaiserpanorama, 1900

|

|

| Phantom Ride |

|

| Rotunda, Leicester Square |

|

| Coronation Procession of King George IV |

|

| Tableau of the procession at the Queen's coronation June 28, 1838 | |

|

Myriorama or tableau polyoptique by Jean-Pierre Brès

(a set of cards that can be arranged in any order) |

↓↓↓

Here are a few of the contemporary moving panoramas that range between overwhelming digital installations of Tomas Saraceno to painted paper scrolls of Adam Cvijanovic.

|

| Tomas Saraceno, Cumulus at Barbican |

|

| Adam Cvijanovic, Rolling Panorama Number 1 |

↓↓↓

The Trip to London scroll box is a story telling gadget that bridged book and upcoming cinema. It's situation is not dissimilar to the hybrid publishing projects emerging today as a result of media arts niche-ing themselves into the book market, such as FakePress and HybridBook. Moving panoramas were defeated by the cinema, of course. Which of the contemporary story telling gadgets are going to stay?

↓↓↓

Printed book sources:

[Egidija]

.jpg)