|

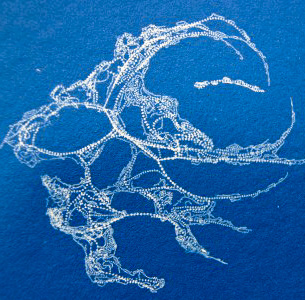

| Installation view of 'Ton âge et mon âge et l'âge du monde', 2005 and 'Nigredo', 1998. |

Recently I got chance to see a retrospective of Anselm Kiefer's book works at the megalithic

Bibliothèque Nationale François-Mitterand in Paris; a building that I love for its sheer audacity (how many other libraries have a wood planted right in the middle of them?).

|

| Library Exterior. |

During the course of my studies I'd heard a lot about Kiefer's books, particularly in relation to their earthy, organic qualities. And because books are often such small, intimate objects, I was keen to see the scale of the works.

I have never seen an exhibition at the Bibliotheque National before, but the gallery was bigger than I expected. The room is made up of an open central space with vitrines of more traditional books and three alcoves on each side, housing the bigger, more physical books.

The first alcove on each side is called 'A Library Of Artists' Books' and have been made to look like archives with their utilitarian grey metal shelving. The shelves hold large (around 1m square) seemingly perfect-bound books. The thick pages have a quality of children's board books, but the content and construction is more akin to a sketch book or a journal. It is easy to imagine that each book is preparation for an artwork. Filed among these are boxes (presumably of books or loose-leaves), sculptural objects and vitrines. The effect is like a behind-the-scenes view of the artist's studio. The huge tomes have a real sense of gravity and even though they can't be read, these reading rooms are still immersive and contemplative spaces.

|

| A Library of Artists Books, 2015 |

|

| A Library of Artists Books, 2015 |

Subsequent alcoves feature large sculptural works - a particular favourite was the installation featuring 'Ton âge et mon âge et l'âge du monde' (2005) and 'Nigredo' (1998) (shown at the top of the page) as the balance between the organic and the bookish in the works seemed just right. Kiefer's work is confident and complex, but the familiar form and the earthy colours lend a warmth to it. This may also on part explain the artist's appeal to those on the

Book Arts course I was on.

|

| Le Livre, 2007 (detail) |

|

| 'Lichtung (Clairière)', 2015 (detail) |

The front and back walls are flanked by large-scale, heavily layered paintings each of which incorporated a book form. I like the symbolic use of the book form within the composition, and although such a deep layering can make paintings very dense for me they certainly had a lot of energy and they enclosed the space very well.

In the vitrines down the middle of the room are a broad range of the artist's books. Many are open and although they can't be touched, the viewer is given a hint as to their contents. In an exhibition like this is not necessary to be able to handle these works, particularly as many are much closer to sculpture than an actual book.

|

| 'Les Reines de France', 1996 (detail) |

Leaving the exhibition I was impressed with how prolific Kiefer is and how consistent his work is. I feel lucky to have had the chance to see the work and particularly in such a relevant context.

'The Alchemy of Books' continues until 7th February 2016.

[Chris]