An instrument of natural magic may reappear as a philosophical instrument, as an instrument of entertainment, or as a practical "invention" in a new guise" (Hankins and Silverman, 1995)

I.

and all we are left with is the world

window vinyls and a set of three artists’ books, including viewing devices

On Wednesday, February 25th, 2015 In a Bookshell opens at Milton Gallery

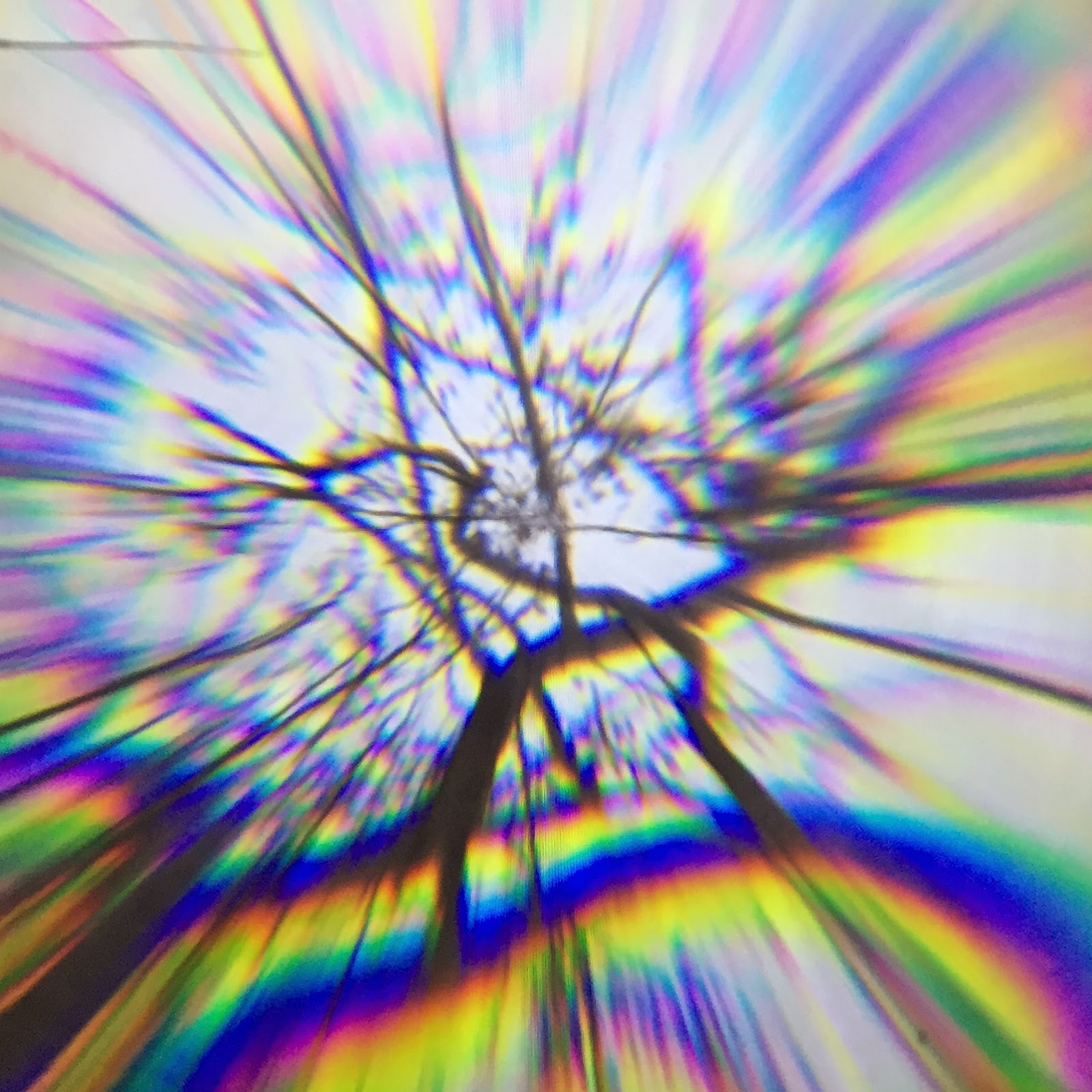

and all we are left with is the world is an installation about perception. It consists of three artist's books and three viewing lenses on the window sill. The books contain scholarly quotes on optics, solipsism, and sensory experience. The lenses guide viewer’s attention to the book and then through it and into the warped space beyond, inviting us to consider the systems of perception as part of our relationship with the surrounding environment.

II.

Books and spectacles go together like horse and carriage, strawberries and cream, oysters and champagne (not quite, but always worth mentioning). Stereotypical geeks carry books and wear glasses. Bill Gates does, for example. Apparently, 53% of university graduates are nearsighted and require reading aids, as compared with 24% of those, who did not even complete secondary education.Glasses, like books, feature often in portraiture of academically accomplished individuals and those would would wish to be considered as such. For ages men have used spectacles as props to embellish the aura of their professionalism in painting and photographs, says William Rosenthal, a collector of visual aids (Rosenthal, 1996).

and all we are left with is the world (see above ↑ ) deals with the metaphysics of looking through a lense and the sensory-perceptual experience of it. Below, ↓ I will mention a few fun, curious and wonderful devices that are part of the history of spectacles.

Apparently, there is no such thing as concise history of spectacles, because there is no agreement as for who and where invented them. Marco Polo observed elderly Chinese use spectacles in 1270. Chinese claim, that spectacles originated in the 11th century Arabia. (1) In the meantime, in Europe Vikings were already able to grind lenses out of rock crystal. However, "proper" first spectacles are often attributed to the Italians of the Veneto region. (2)

With the invention of mechanical printing and subsequent rapid growth of publishing industries, the need for reading devices increased and inexpensive spectacles became widely available from peddlers. Finally, in the 1600s the spectacles as we recognise them now were born: the two lenses were finally fixed to a rigid bridge allowing them to stay in place on top on the nose. (1)

Here are a few fun, curious and wonderful devices from the history of spectacles:

a.)

↓

From 17th century spectacles were were sold by instrument makers, who also traded in compasses, zograscopes, telescopes and other fantastical "scientific toys", that coexisted together with a range of other more or less useful instruments. Among them, were faceted lenses - multiplying glasses - which were used for entertainment and were treated as a luxury commodity: they were produced in expensive materials and were generously decorated (Stafford and Terpak, 2001).

b.)

↓

c.)

↓

Personally, I find optical fans most fascinating! Some fans had tiny telescopes set into the centers, others had lorgnette frames folding away into the guardsticks. However, the most exciting were spyhole fans.

For short sight a single concave lens could be mounted in one of the spyholes, effectively forming a Quizzer or Quizzing Glass. This was then further developed into a Galilean telescope by mounting a convex lens in the outer guardstick and a concave lens in the inner guardstick. Lining up the holes in the intervening sticks, when the fan was closed and the blades rested upon one another, produced a simple tube with a lens at each end. The resulting spyglass could even be adjusted for focus by varying the separation of the closed sticks. (3)

III.

Lens devices used in art, including book art, are varied, but not abundant. Here are a couple of the works that I found most interesting. I have chosen one work of each (kind of) category.

a.) installation lens/vision

↓

Haruka Kojin explores the distortion of reality through her piece "Contact Lens". Two types of lenses are used, one completely flat and clear and the other with a warped surface to create interconnected circles of varying sizes. As the light travels through the acrylic, the images on the other side are flipped and contorted, changing the experience of the space. since the elements are clear with no frames or distinct features of its own, the physical material merges into the environment, only visible through the transformation it causes.

b.) installation lens/light

↓

IPOcle by Candas Sisman is a light installation produced with lenses, light, mirror, sound, container, and fog. It simulates the way we perceive the physical reality and the various layers, variables, cycles that are present in this process of perceiving. These perceptions draw our perceptual schemas and these schemas in turn shape the reality we perceive. Our perceptions and what we perceive, therefore, constantly reshape call each other into being, as in a vicious cycle. At this point, how can we define what reality really is, what constant can we refer to, and aren’t we supposed to look at this issue in a more holistic and intertwined manner?

c.) book lens/vision

↓

c.) artefacts lens/surprise

↓

A Glimpse of Heaven by Keith Lo Bue is an optical device made of industrial shop ruler, clockspring, brass, brass hardware, steel, engraving, book end paper, glass bead, lenses, paper, text, soil. Keith Lo Bue's works connect disparate phenomena: reality and surreality; preservation and decay; memory and forgetting.

.

An instrument of natural magic may reappear as a philosophical instrument, as an instrument of entertainment, or as a practical "invention" in a new guise" (Hankins and Silverman, 1995)

Sources:

(1) Ophthalmic Heritage & Museum of Vision

(2) The College of Optometrisists

(3) Online Museum and Encyclopaedia of Vision Aids

Hankins, Thomas L. and Robert J. Silverman. 1995. Instruments and the Imagination. Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press. p. 221.

Rosenthal, William J. 1996. Spectacles and Other Vision Aids. San Francisco, CA: Norman Publishing. p. 358.

Strafford, Barbara Maria and Frances Terak (eds.) 2001. Devices of Wonder: from the World in a Box to Image on a Screen. Los Angeles: Getty Publications. p185.

[Egidija]